In the Autumn of 1951, my future lay in the balance. At 16, many boys from my grammar school left to go into fulltime employment. Despite the lack of money at home, I was able to stay on, that is, to go into the Sixth Form for two years to prepare for A Levels, the necessary qualification for getting into university.

In the Autumn of 1951, my future lay in the balance. At 16, many boys from my grammar school left to go into fulltime employment. Despite the lack of money at home, I was able to stay on, that is, to go into the Sixth Form for two years to prepare for A Levels, the necessary qualification for getting into university.Your life changes once you are in the Sixth Form. Quite apart from your chosen specialist subjects, you have a great thirst to expand your knowledge, to acquire what the Italians call your “bagaglio culturale”. Alongside this, you acquire what some people have called “a Sixth Form vocabulary”, learning words like egregious and cathartic and phrases like Gordian knot and Occam’s Razor to add an air of erudition to your adolescent intellectual mumblings.

To help me to acquire my cultural baggage, I was introduced to the works of two notable polymaths. One was Lancelot Hogben, who was the driving force behind a series called “Primers for the Age of Plenty”. As a good Marxist, he saw the need to provide useful Knowledge (with a capital K) to the masses, and wrote, or caused to be written, books with titles like "Mathematics for the Million" and "Science for the Citizen". The book in this series that made all the difference to me was “The Loom of Language”, a gallop round the world’s languages ending up with a series of strategies for rapidly acquiring a batch of them. I particularly liked the chapter called “The Diseases of Language”, in which the good Hogben rails against highly inflected languages like Lithuanian and Russian. What is the use of all those endings, all those declensions and conjugations? he asks (I had to part company with him here: after years of Latin, I LOVED inflections, and shortly after leaving university started to learn Russian).

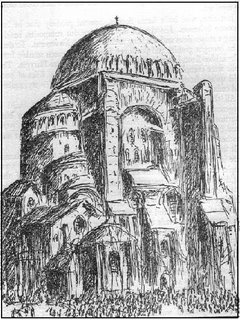

The other guru of the age was Hendrik van Loon, a most prolific author. The book of his that made me catch fire was called “The Arts of Mankind” (originally "The Arts", published in 1937). The book took a Hogben-style romp through the history of the arts (which for van Loon included the crafts), accompanied by many line drawings that I loved. I loved them because they were accessible: I felt I could do drawings like those. And indeed I did.

One that most captured my imagination was a line drawing he did of the basilica of Santa Sofia in Constantinople (now Ağya Sofia in Istanbul). I stared at that drawing till my eyes watered, I read the text again and again, and I even tried to copy the van Loon drawing. But I knew that I would never ever see the real thing. It would only be a dream in my head.

One that most captured my imagination was a line drawing he did of the basilica of Santa Sofia in Constantinople (now Ağya Sofia in Istanbul). I stared at that drawing till my eyes watered, I read the text again and again, and I even tried to copy the van Loon drawing. But I knew that I would never ever see the real thing. It would only be a dream in my head.And then, against all my expectations, I found myself many many years later in Turkey doing a lecture tour, part of which included Istanbul. I had to see Santa Sofia. Of course it had ceased to be a Christian basilica with the taking of Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453, after which it became a mosque. As I approached it, I felt a wave of disappointment washing over me: it seemed drab, tawdry even, and it was lost in a mess of other buildings. And then I entered. The magnificence of it took my breath away. I cried. Literally. Tears running down my cheeks as I tried to absorb its beauty. It was beyond anything I had ever imagined. It was as much as anything a monument to the human spirit. It renews your faith in mankind to see what beauty we are capable of creating. Moments like that don’t come often in your life.

Santa Sofia is neither a Christian basilica nor a Muslim mosque now. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk wisely decreed that it should be a museum. This means that, according to your taste, you can read the inscriptions in Arabic praising Allah, or study the frescoes celebrating the Christian saints. Or both. Or simply wonder at the human spirit that inspired this House of God.

I still have my copies of Hogben’s Loom of Language and van Loon’s Arts of Mankind. Long dead, mostly forgotten, but they will always be heroes to me.

4 comments:

I think Atatürk was very wise to designate it as an historical building rather than a religious one. That way there can be no quarrel about whether it's Christian or Muslim. And anyone going there is free, as I said in my blog, to worship their God in their own way. If you go, do go up to the galleries and look at the frescoes: they are wonderful. It doesn't matter that they are Christian: they are testimony to the best in human beings.

I think I was raised on Van Loon too: The Child's History of the World (right title?), Child's Geography ditto, and weirdest of all, Van Loon's Lives, a series of necromantic dinner parties hosted by the narrator and assisted by Erasmus.

I had forgotten about the Van Loon dinner parties, where he entertained famous figures from history. The weirdest part was the attention he paid to the food he prepared, tailored to what he imagined would be the particular taste of each particular guest. Thanks for reminding me, Charles. I must see if I can find a copy at the next second-hand bookfest in Cambridge.

Oh yes, the menus.

The book did stick with me: I still, for example, remember the two Orthodox monks who squabbled over the divine nature of Jesus and ended up rolling on the floor, wrapped in the tablecloth.

And it all happened in Holland on the eve of World War II, which gave the book an eerie cast in retrospect.

Chas (pr. "chaz" -- only my mother called me Charles)

Post a Comment